Meet Conrad and Davis

This is engineer Frank Conrad’s amateur AM station as it was in 1920 in the workshop-garage of his home in the Pittsburgh suburb of Wilkinsburg. That summer, at the request of his bosses at Westinghouse, he went to work on a more powerful commercial station for the company, KDKA.

Westinghouse Electric sparked the new age of electronic mass media when it launched KDKA radio in Pittsburgh on Nov. 2, 1920, put its full weight behind the commercial venture, and sped past other pioneering efforts.

It was a bold move that quickly showed the potential of radio as a business and transformative cultural force.

Two Westinghouse employees were chiefly responsible for the company’s startup, Frank Conrad and Harry P. Davis. Conrad supplied the technical know-how; Davis, the business acumen and money.

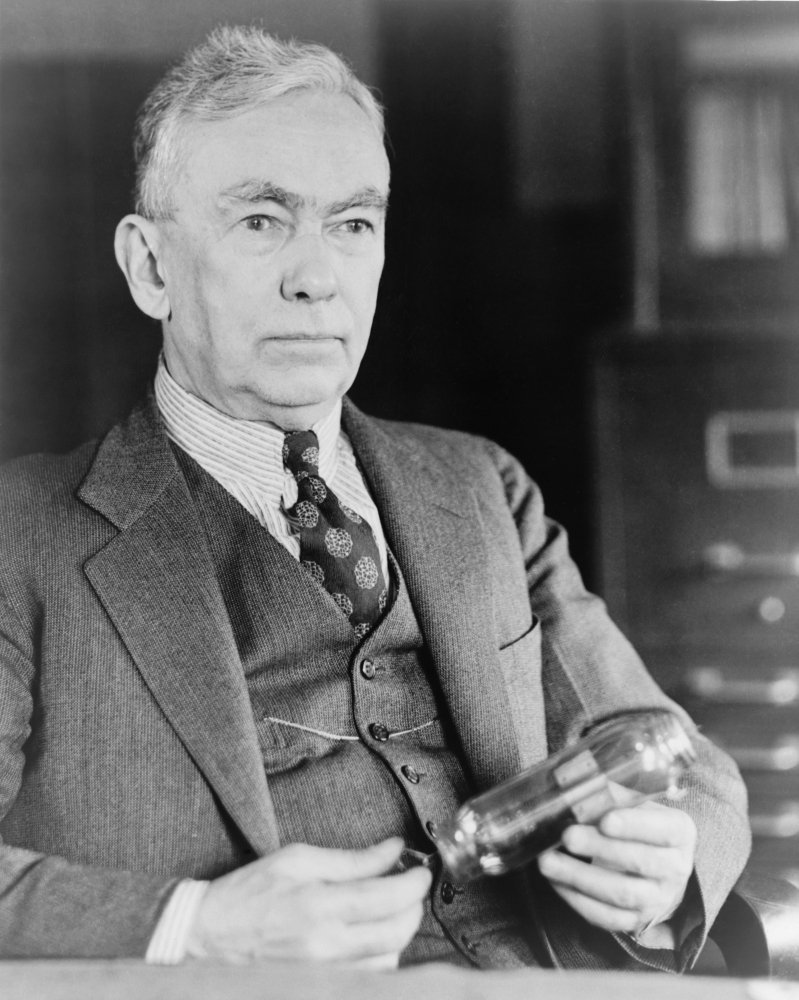

THE ENGINEER

With only a seventh grade education, Conrad built the station that triggered a revolution.

At the time Westinghouse jump-started broadcasting, Conrad was working for the company as assistant chief engineer at its East Pittsburgh plant on a number of electrical and wireless communications projects.

But for several years, he had also been experimenting in his off hours with what we now know as radio. From the garage-workshop of his Wilkinsburg home, Conrad built a transmitter and broadcast his voice, live music and records to a delighted and growing cadre of local wireless enthusiasts with simple receivers.

His listeners would call or write asking for more news and music. When he became swamped with these requests, he decided to broadcast regular, scheduled programs. And when he ran out of his own records, he borrowed from a Wilkinsburg music store in exchange for mentioning the store on the air. (The store owner soon discovered that records played on Conrad’s station sold better than others.)

THE EXECUTIVE

Davis had to talk his bosses into betting heavily on broadcasting. The gamble paid off big.

Westinghouse profited from supplying the U.S. military with wireless two-way radios during World War I. But after the war ended in 1918, the company found itself with a large investment in wireless technology and unsure how to capitalize it on it. Davis, who was the vice president of engineering and manufacturing, tackled the problem.

Aware of the popularity of Conrad’s amateur garage broadcasts, Davis began to follow his activity more closely. A Sept. 29, 1920, a newspaper ad proved to be decisive. That day, the local Horne’s department store described the reception of a Conrad broadcast by the store’s newly-installed radio receiver. More important, it offered radios for sale to the public.

Davis convinced himself that a service with a full and regular slate of programming would be a lucrative new business for Westinghouse. With newly acquired radio patents, it could mass produce reliable and easy-to-use receivers and make a fortune selling them.

He had to convince his bosses who were still thinking that radio was for private, one-to-one communications, a more efficient form of telegraphy. It was a tough sell, Westinghouse President E.M. Herr later recalled in a newspaper interview.

“It was Davis who got the idea from the engineers…who were urging activity from the technical standpoint, and it was Davis who saw the larger commercial significance and possibilities and was persistently insistent until he got what he wanted.

“In talking over these matters Davis told me he had taken liberties with authority realizing that if things didn’t work he would be personally responsible for a catastrophe. But he had the courage of his convictions.”

Davis finally got the OK. He and his “radio cabinet,” including Conrad, set in motion plans to construct a transmitter, apply for a license and inaugurate the station by broadcasting the 1920 elections returns. Since then, KDKA has never stopped broadcasting and electronic media has spun off into many more powerful directions.

Conrad was a self-taught engineer whose formal schooling ended after the seventh grade. Yet, during his career, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science from the University of Pittsburgh and was the recipient of numerous awards including the Edison Medal. By the time he died in 1941, he held more than 200 patents.

Davis continued to play a key role in broadcasting in the aftermath of KDKA. He championed the idea of radio networks. During the 1920s, Westinghouse was part owner of RCA and in 1926 he was made chairman of RCA’s National Broadcasting Company, the nation’s first radio network, while maintaining his job at Westinghouse. He held both positions until his death in 1931.

KDKA Turns 100.

On Nov. 2, 2020, the NMB joined Duquesne University, Pittsburgh area officials and representatives of the broadcasting industry in celebrating the 100th anniversary of KDKA’s inaugural broadcast on the site of the station’s original studio and transmitter. For the occasion, the Library of American Broadcasting Foundation produced this video featuring KDKA newsman Larry Richert. Click in and see and hear “the way it was” 100 years ago.