City of Genius

As a Pittsburgh institution, we take special pride in celebrating not only KDKA founders Frank Conrad and Harry P. Davis, but also other electrical and media innovators with strong ties to the city — George Westinghouse, Nikola Tesla, Reginald Fessenden and Vladimir Zworykin. All four made tremendous contributions to media; all four are members of the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Va.

Let’s meet them.

GEORGE WESTINGHOUSE AND NIKOLA TESLA: There would be no electronic mass media (and much of the rest of the modern world) if not for a ubiquitous, plentiful and reliable supply of electrical power. Much of the credit for its creation in the late 19th century goes to Pittsburgh inventor and industrialist George Westinghouse and eccentric, but brilliant inventor Nikola Tesla.

In the early 1880s, the great American inventor Thomas Edison was racing ahead, building a patchwork of small power plants around the country using direct current (DC) technology. The more plants he built, the more of his light bulbs he could sell.

THE ENTREPRENEUR

Westinghouse made a big bet on AC electricity, beat Thomas Edison and helped light up the night.

Westinghouse took notice. In 1886, he created Westinghouse Electric and began challenging Edison with what he felt was a better technology that he had imported from Europe – alternating current. AC’s great advantage is that it could be distributed over long distances. One big power plant could serve vast regions. Each of Edison’s direct current plants could only serve customers within a few city blocks. His patchwork approach was dictated by the limits of DC.

AC had one big problem. It was not compatible with industrial motors, the second most important application (behind lighting) of the new electrical systems. Fortunately, a little known Serbian inventor with big ambitions , Nikola Tesla, had solved the riddle with a polyphase induction motor that ran on AC. When Westinghouse learned of it, he bought Tesla’s patents and hired him to come to Pittsburgh to work alongside him and other engineers in developing a complete AC system.

Armed with Tesla’s patents and expertise, Westinghouse beat Edison in the so-called current wars, announcing to the world the wonders of AC power at the World Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893. A few years later, he and Tesla flipped the switch on a hydroelectric generating plant at Niagara Falls that sent power to Buffalo and later along lengthening lines to New York City.

Before he turned to electricity, Westinghouse was already a wealthy businessman, having invented and brought to market the air brake that took much of the risk out of operating trains. But after a good long run, he lost control of his holdings during the recession of 1907. He died in 1914, just six years before the company that still bore his name plunged into radio.

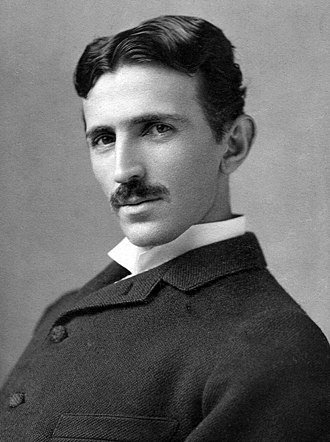

THE WIZARD

Telsa, a Serbian immigrant, supplied the induction motor, the missing piece in Westinghouse’s AC power system.

Tesla, who had emigrated to the United States as a young man, became wealthy from the sale of his patents to Westinghouse. He established himself firmly on the New York City scene as an technical wizard -- part inventor, part showman. While the induction motor would be his greatest contribution to the modern world, he dabbled in many related fields, including wireless communications, robotics and X-rays.

He was among the first to appreciate the potential of wireless technology, believing that it could be harnessed not only for communications, but for electrical power distribution. In a patent case to which he was not a party, the Supreme Court in the same year he died recognized his important contributions to early wireless communications.

However, rather than pursue wireless using the electromagnetic spectrum – radio waves – as Marconi and others did, he spent a small fortune trying to develop a system that would use the earth itself as the medium. The approach proved a technological dead-end.

In his later years, Telsa became a futurist of sorts, predicting many technological developments of our modern world and has today reemerged as an inspiration to inventors and tech entrepreneurs. At the time of his death in 1943, he held many patents, but they did not keep him from falling into a genteel poverty. He died while living in a New York hotel on a small Westinghouse pension.

REGINALD FESSENDEN: Fessenden, a native of Quebec, Canada, came to Pittsburgh in 1893 to serve as the head of the electrical engineering department at Western University (now the University of Pittsburgh.) While here, Fessenden read of the radio experiments that Guglielmo Marconi was conducting in England.

THE PROFESSOR

The one-time Pittsburgh professor gave voice to wireless telegraphy and set the stage for broadcasting.

He began experimenting at a lab at the Allegheny Observatory. Marconi’s system could only transmit and receive dots and dashes—Morse code. But Fessenden’s goal was to transmit the human voice and music.

To accomplish this, he devised the theory of the "continuous wave"—a means of superimposing sound onto a radio wave. Fessenden later put the theory into practice and reportedly made the first long-range transmissions of voice on Christmas Eve 1906 from a station at Brant Rock, Mass. It is said that ship radio operators hundreds of miles out in the Atlantic heard the program.

VLADIMIR ZWORYKIN: At the same time radio was taking hold, a young Russian immigrant named Vladimir Zworykin was developing a system of wirelessly transmitting sound and pictures—television. Early conceptions of television focused on a mechanical scanning system with motors and large rotating disks. This type of television generally produced small pictures and required heavy, bulky equipment. It would prove impractical for home use.

THE TELEVISIONARY

Many invented television. But two names stand out from the rest: Farnsworth and Zworykin.

Zworykin, while working at Westinghouse and living in Swissvale in the 1920s, conceived an all-electronic system with iconoscopes and kinescopes, the forerunners of today’s TV cameras and picture tubes. He patented the system in 1923. Six years later, he demonstrated a crude version of the system for the Westinghouse brass. It didn’t go well — or well enough — to dissaude the company from its interest in a mechanical system.

In 1929, he found a far more receptive patron in RCA chief David Sarnoff, who hired Zworykin and set him up with research labs in Camden, N.J. Drawing on RCA’s deep pockets, he developed a fully functional TV system that was introduced to great acclaim at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Of the many who worked on TV in the 1920s and 1930s, he and independent inventor Philo T. Farnsworth derserve the largest portion of credit for bringing it to fruition.